Having a 'Third Thumb' can cause the brain to assess the hand in a different way, say UCL researchers who experimented on the usage of a robotic extra thumb.

In an article titled "Robotic 'Third Thumb' use can alter brain representation of the hand," a team of researchers trained people to use a robotic extra thumb attached to their hand. The results showed that the people could successfully carry out tasks such as building a tower of blocks with one had (the hand with the extra robotic thumb).

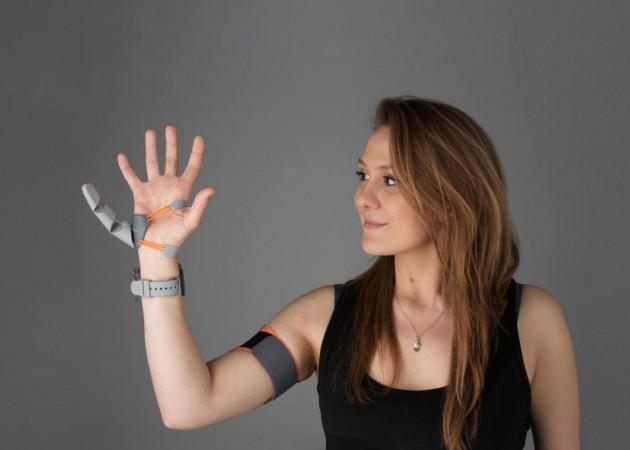

In addition, the researchers also found out that the people who were trained, began to feel like the 'thumb' was part of their body. The designer of this contraption, Dani Clode, began developing this device as part of an award-winning graduate project at the Royal College of Art. She was attempting to redefine prosthetics as an extension of the human body rather than a replacement for a missing feature.

The Third Thumb is 3D-printed and worn on the side of the hand opposite the user's real thumb, making it easy to customize. It is controlled by pressure sensors on the bottom of the big toes, which are linked to the wearer's feet. Both toe sensors are wirelessly attached to the Thumb and monitor various movements of the Thumb by responding quickly to subtle pressure changes from the wearer.

Twenty participants were taught to use the Thumb over the course of five days, during which time they were also allowed to take the Thumb home after training to use it in real-life situations. This resulted in a total of two to six hours of wear time each day. The participants were compared to a control group of ten people who completed the same training while wearing a static version of the Thumb.

Coordination between extra thumb and hand

Participants were taught to use the Thumb during regular sessions in the lab, working on activities that helped them improve coordination between their hand and the Thumb. They did activities such as picking up several balls or wine glasses with one hand. They soon learned how to use the Thumb and were able to develop their motor control, flexibility, and hand-Thumb coordination as a result of the exercise. Participants were able to use the Thumb even when they were distracted, such as while making a wooden block tower when solving a math problem, or while blindfolded.

The researchers used fMRI (Functional magnetic resonance imaging) to scan the participants' brains before and after the training as they moved their fingers separately (they were not wearing the Thumb while in the scanner). The researchers discovered small but important changes in how the brain perceived the hand with the Third Thumb (but not the other hand). Each finger is viewed differently in our brains; however, the brain activity pattern corresponding to each finger became more similar among the study participants.

Some of the participants were scanned again a week later, and the changes in their brain's hand area had faded, suggesting that the changes were not long-term, but further study is needed to support this.

![Budget 2026-27 aimed at empowering poor and increasing farmers' income: PM Modi [Watch]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/827940/budget-2026-27-aimed-empowering-poor-increasing-farmers-income-pm-modi-watch.jpg?w=220&h=138)