The Arctic Permafrost, a layer of ice in the Northern Tundra that has been permanently frozen since the last ice age, has started to slowly melt due to climate change and global warming. This thawing could free large amounts of methane, which is a greenhouse gas.

Results of a new research paper, funded by NASA has found that the expected gradual thawing of Northern ice and the release of greenhouse gases could actually be fast-tracked by incidents of "abrupt thawing", a relatively unknown process, said NASA.

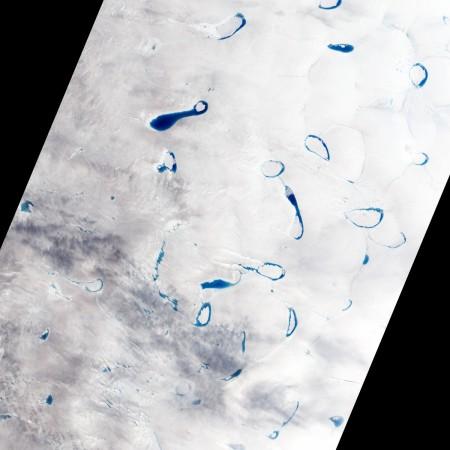

Abrupt thawing, says the space agency, happens below the surface of a specific type of Arctic lake called a thermokarst lake. These lakes form as permafrost continues to thaw.

The Northern Tundra stores possibly the largest natural reservoir of organic carbon on Earth, trapped in the frozen soil. If this soil starts to defrost, microbes that live in the soil will start to work on the carbon and convert it into carbon dioxide and methane. These gases have a major part to play in the current climate scenario. While carbon dioxide is seen as the biggest culprit among greenhouse gases, methane is about 30 times more potent at trapping heat, notes an SD report.

The first author of the study Katey Walter Anthony said, "The mechanism of abrupt thaw and thermokarst lake formation matters a lot for the permafrost-carbon feedback this century." Anthony led NASA's Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (AboVE), a study that stretched over ten years and was carried out in an attempt to calculate climate change's effects on the Arctic.

Anthony explained that we don't have to wait 200 or 300 years to get these large releases of permafrost carbon. "Within my lifetime, my children's lifetime, it should be ramping up. It's already happening but it's not happening at a really fast rate right now, but within a few decades, it should peak," she explained.

The team used computer models and field measurements to simulate the rate of thaw and the creation of thermokarst lakes. As a result, they found that previous estimates of abrupt thawing and permafrost-derived greenhouse warming were off by a lot. The current estimates put it at more than double the previous ones, says the report.

Researchers also found that this abrupt thaw process actually accelerates the release of ancient carbon deposits trapped in the frozen soil by 125 percent to 190 percent when compared to gradual thawing. Additionally, researchers say that even in a future where humans reduce their global carbon emissions drastically, it might not make a difference and large methane releases from abrupt thawing of permafrost are still likely to occur.

The results of the AboVE study was first published in the journal Nature Communications.