The research team of NASA's Juno space probe orbiting Jupiter originally planned to reduce the orbiting period of the spacecraft from 53 days to 14 days. But those plans are now shelved due to a technical glitch in the spacecraft's propulsion system.

Also Read: Zealandia: Geologists discover the 8th continent!

The Juno spacecraft, built by Lockheed Martin and operated by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, has been orbiting Jupiter since July 2016. It has an orbiting period of 53 Earth days. The plan to reduce this period to 14 days with the help of an engine burn has now failed because of a glitch in the propulsion system. There is some issue with two helium valves of the Juno rover, which has now forced NASA to cancel the target to reduce the orbiting period.

"During a thorough review, we looked at multiple scenarios that would place Juno in a shorter-period orbit, but there was concern that another main engine burn could result in a less-than-desirable orbit," said Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

"The bottom line is, a burn represented a risk to completion of Juno's science objectives," he added.

The Juno mission, worth $1.1 billion, was launched in 2011 to collect data about Jupiter's structure, composition, and its gravitational and magnetic fields, which it collects during its flybys.

On February 2, the spacecraft was closest to Jupiter's outer atmosphere -- around 4,300 kilometres (2,670 miles).

The Juno mission originally planned to complete more than 30 close flybys with an orbiting period of 14-days, but even if it continues the mission through July 2018, it can only make 12 close pass-bys due to its 53-day path.

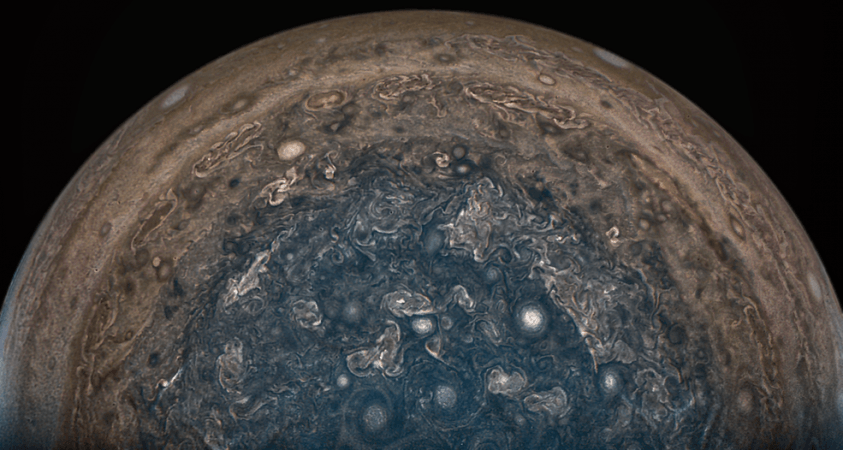

So far, the spacecraft has completed four close flybys, which revealed that the auroras and magnetic field of Jupiter are stronger than they were previously thought to be. The funds of this mission are expected to run out by July 2018 and the team might not extent the mission further.

"Another key advantage of the longer orbit is that Juno will spend less time within the strong radiation belts on each orbit," said Juno's principal investigator Scott Bolton.

The details from previous Juno missions are still being analysed by researchers. The space probe is likely to achieve the targets of this mission in the longer trajectory, NASA officials say.

"Juno is providing spectacular results, and we are rewriting our ideas of how giant planets work. The science will be just as spectacular as with our original plan," Bolton said.

The next flyby by Juno is likely to be made on March 27.