It happens quite often that a person of eminence are some times loved and hated in equal measures, depending on the way you perceive.

In the case of Shi Zhengli, a virologist of international repute, it is no different-at least in her home country- China.

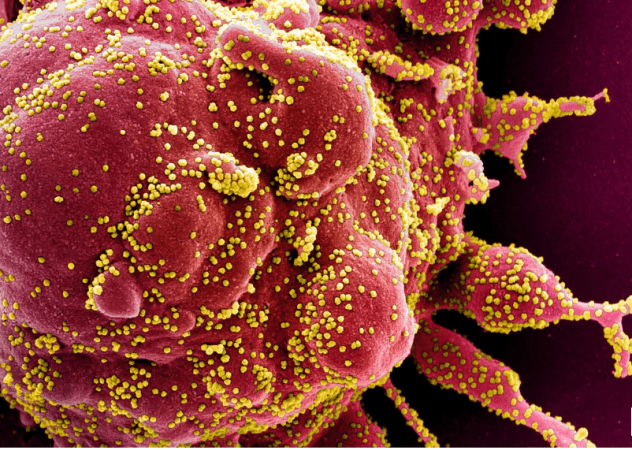

Nicknamed "Bat Woman", for her virus-hunting expeditions in bat caves over the past 16 years, Shi is credited with discovering the link between SARS-COV and bats. She found the link after the 2002 SARS pandemic during which more than 8000 people were infected, and over 800 died.

Coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan

When the samples from infected patients arrived at Wuhan Institute of Virology in late December 2019, Shi was attending a conference in Shanghai. There she got a message from her boss at WIV asking her to, "Drop whatever you are doing and deal with it now," quotes the reputed journal The Scientific American.

The Wuhan Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had detected a novel coronavirus in two hospital patients with atypical pneumonia, and it wanted WIV to investigate it.

Tad worried, a tad confused, on her way back to Wuhan, Shi wondered if municipal authority got it wrong, "I had never expected this kind of thing to happen in Wuhan, in central China," she says.

Race to map viral genome sequence

When she reached her laboratory, she and other scientists rushed to map the sequence of the virus. The reason for their concern was based on two grounds:

First, they didn't expect Wuhan to be the ground zero of any zoonotic outbreaks-coronavirus jumping from animals to humans, particularly bats, a known reservoir for many viruses.

Second, if coronavirus were the real culprit, would it had been possible that they "leaked" from WIV lab?

At WIV, Shi and her team swiftly mapped the genome sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 received from the patients at a hospital and compared it with the sequence of the virus they were testing at the laboratory.

To their relief, the result showed that none of the sequences matched with the viruses the scientist at WIV were testing. "That really took a load off my mind," she says. "I had not slept a wink for days."

By January 7, after mapping, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, and checking for antibody, the Wuhan team found out that the new coronavirus is indeed a culprit and has caused the disease in the patients.

Click here for all coronavirus stories

Tracing the coronavirus in bat cave

The reason why Shi didn't think Wuhan to be the possible ground zero of the zoonotic outbreak was her experience with earlier experiments she did to find the pathogens responsible for the SARS outbreak in 2002.

During her investigation, Shi had found areas like Shitou Cave on the outskirts of Kunming, the capital of Yunnan in southern China, could emerge as the centre of the zoonotic outbreak.

The reason for her belief was her findings of bat-borne coronaviruses with incredible genetic diversity with some potent enough to infect human lungs cells in a petri dish, cause SARS-like disease, and could evade drugs that work against SARS.

Her team had discovered a coronavirus from horseshoe bats in the Shitou Cave with viral genome sequence 97% similar to the ones that led the outbreak of SARS in 2002.

Shitou Cave in Yunnan the possible ground zero

Her opinion of Shitou Cave to become the possible ground zero for the outbreak was fostered by the fact that a big number of villages were located within the 1 km of radius from the caves where virus-laden bats roosted.

The vicinity of the human population with those deadly bats, according to Shi, was a highly potent scenario of leading to a zoonotic outbreak. Shi says, "you don't need to be a wildlife trader to be infected."

Mapping the viral genome sequence at WIV

Back at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, her peers released a report on their finding in journal Nature, titled A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat.

Soon enough after the report was published, WIV director Yanyi Wang, sent a mail to all those involved in the study asking everyone to not disclose any information about the disease on social media, journal or even with any government agencies.

The WIV director in the email cautioned that "inappropriate and inaccurate information was causing general panic," reported Daily Mail.

Backlash

Though WIV published no other report on the matter at any public forum, public in China by then had started lashing out against Shi for letting the virus escape from WIV. She had become one of the most hated people in China.

She then took to microblogging site in China to dispel doubts about WIV "releasing" the virus.

She posted: "I swear with my life (the virus) has nothing to do with the lab."

Outbreak not incidental

The study of the coronavirus reveals that SARS-like outbreak was neither an aberration nor incidental.

Given that the genomic sequence of the virus in the patients are very similar, and most of the patients develop mild symptoms, scientists suspect that the pathogen might have been around before the first few severe cases caused alarm. "There might have been mini outbreaks, but the virus burned out" before causing havoc, according to Ralph Baric, a virologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

"The Wuhan outbreak is by no means incidental," Baric says. There was an element of inevitability to it.

Zoonotic spillover

According to scientists in the field of microbiology and virology, mixing of strains of virus keeps on happening in animals. It's only when the gap between wildlife and humans decreases the chances of zoonotic spillover increases.

The emergence of the current outbreak shouldn't give us a false sense that China is the only hotspot. Scientists say that new pathogens emerge at places where dense population is changing the landscape.

Developing countries like India, Brazil and Nigeria are at great risk too.

As dense forest and wildlife habitation are being razored down to make way for constructing buildings, farming, and digging mines, animals are losing their habitation area. This give rise to chances of zoonotic spillovers.

Hybrid virus and preventive measures

One of the aims at labs like WIV, is to study the virus and the disease it may cause, in order to find a solution in treating and preventing those diseases. But waiting for the outbreak to begin the search for treatment is too dangerous. For this reason, scientists do develop hybrid virus called "chimeric virus" which they say are future forms of virus.

Chimeric virus helps scientists to study its ability to mutate and infect humans, and as a result, develop treatments for the disease caused by the virus.

"The hybrid virus allowed us to evaluate the ability of the novel spike protein to cause disease independently of other necessary adaptive mutations in its natural backbone."

As scientists believe it's inevitable that with globalisation and easy connectivity, these viruses with deadly strain would reach places around the globe in a short time, and unless there is a pharmaceutical drug or vaccine to control it, a large scale pandemic can't be avoided.

Efficacy of remdesivir against COVID-19

It is no surprise then that Shi was one of the first few scientists to promote antiviral drug remdesivir as an effective drug in treating COVID-19. In fact, she also filed a patent application on behalf of China.

Even though enough clinical date on remdesivir efficacy is awaited around the world, Shi warns more deadly SARS-like viruses are out there in the wild. "What we have uncovered is just the tip of an iceberg," Shi says.

According to one estimate by researches involved in similar projects to find coronavirus in bats, say "that there are as many as 5,000 coronavirus strains waiting to be discovered in bats globally."

Her decade long study on bat-borne coronaviruses has given her insight and she sounds certain when she says that there will be more coronavirus outbreaks. "We must find them before they find us," Shi says.