A Chinese scientist has claimed that he has helped birth the world's first-ever genetically edited babies — a pair of twin girls. Their DNA was reportedly altered using a new and powerful tool called CRISPR-Cas9. He Jiankui says it is now possible to rewrite the very blueprint of life.

If He Jiankui's claims are true, this development would be a profound leap in the field of genetics as well as scientific ethics, points out an AP report.

An American scientist has also reportedly taken part in the experiment in China. Gene editing on humans is banned in the US, notes the report, because modifying genes and making changes in the DNA could possibly move from one generation to the next and there is an ever-present threat to the health of other genes as well.

It is said that many mainstream scientists feel like gene-editing humans are too unsafe to try, and others are said to have denounced this Chinese research as it being akin to human experimentation.

He Jiankui of Shenzhen, who goes by "JK", the scientist who carried out this research, told AP that he modified the embryos for seven couples when they were undergoing fertility treatments. So far, says JK, it has resulted in one pregnancy.

JK says the goal was not to cure or prevent any diseases that a child might inherit but to try and give it a trait that a small percentage of humans naturally have—the ability to possibly resist future HIV infections. HIV is responsible for AIDS and a cure for the disease is yet to be found.

He claims that the parents involved in the study have declined to be interviewed, and also refused to disclose the location of where the research was carried out.

AP has also said that, so far, there is no independent analysis or any confirmation of He and his work, and it is yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal so that it can be thoroughly vetted by other researchers and experts in the field. JK spoke of his study this week in Hong Kong, notes the report, to one organizer of an international conference on gene editing and has also spoken to the AP on what his research has found so far.

"I feel a strong responsibility that it's not just to make a first, but also make it an example," He told the AP. "Society will decide what to do next" in terms of allowing or forbidding such science.

Fellow members of the scientific community have strongly condemned He's work.

It's "unconscionable... an experiment on human beings that is not morally or ethically defensible," said Dr Kiran Musunuru, a gene-editing expert from the University of Pennsylvania.

"This is far too premature," added Dr Eric Topol, who heads the Scripps Research Translational Institute in California. "We're dealing with the operating instructions of a human being. It's a big deal."

George Church, from Harvard, however, defended this research. More so because it deals with HIV, the disease, he says, is "a major and growing public health threat."

"I think this is justifiable," Church said of trying to combat it.

HIV, according to the WHO's Global Health Observatory Data, is a global epidemic where more than 70 million people have been infected and about 35 million people have died.

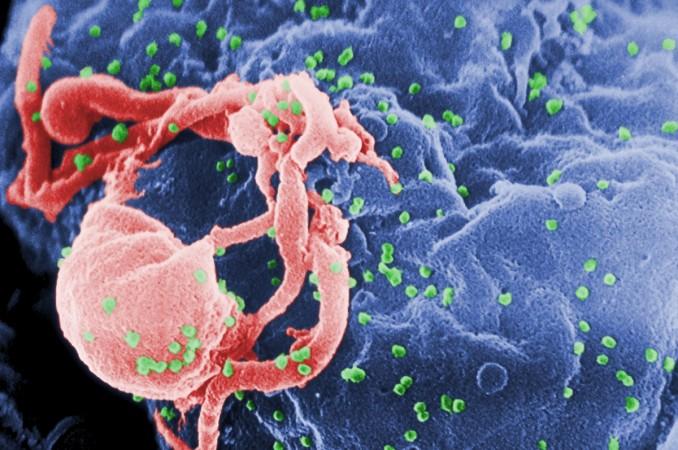

Gene editing is a process of modifying strands of DNA that controls the entire body. It can be easily edited using a tool called CRISPR-Cas9. It can effectively perform operations on the DNA directly and theoretically, one can supply a needed gene to the strands or even disable the one that's causing problems, notes AP.

JK said he was able to gain practice by editing mice, monkey, and human embryos in labs for several years. He has even applied for patents for some of his methods as a result of his study.

Embryo gene editing for HIV was chosen because it is a major health issue in China. As to how exactly JK has gone about it, he says that he sought to disable the CCR5 gene. It forms something of a protein doorway which allows HIV to enter a cell, eventually reproduces rapidly and take over the immune system.

All the men involved in this project were HIV positive and all the women were not. The target of the gene editing research, however, was not aimed at preventing a risk of transmission. All the male subjects had their HIV infections suppressed by HIV medicines that are now easily available all over the world and there are ways to keep the infection from spreading to their babies that already exist and they do not involve and gene altering.

The research, however, was to offer HIV positive people a way to have children with immunity to the deadly virus.

JK then went on explain the process—gene editing, he says, was carried out during IVF or lab fertilisation. First, the sperm cells were "washed" to separate them from semen, this is where HIV could possibly be found. A single sperm cell, he says, was placed into a single egg and an embryo was thus formed. It is at this point that the gene editing was carried out.

At around 3 to 5 days old, a few cells were taken from the embryo and checked if it was possible to edit them. At this point, couples were told that they could choose whether to use edited or unedited embryos for their pregnancy attempts. In the research, says JK, 16 out of 22 embryos were edited. Eleven edited embryos were then used in six implant attempts before one of the couples were able to achieve the twin pregnancy, He said.

So far, one of the twins had both copies of the edited gene-altered while the other twin had just one altered. There is also no evidence of any harm to the embryos' other genes.

In general, those with one copy of the gene can still contract HIV, but there are chances that their rate of decline, when it comes to health could happen more slowly if they do.

A number of scientists have so far reviewed data that He gave to the AP, notes the report. They have said that the tests so far are insufficient. There is not enough evidence to conclusively state whether or not the editing worked so far as to rule out harm caused to the embryos.

"It's almost like not editing at all" if only certain cells go through alteration, HIV infection can still occur, Church said.

The use of that embryo suggests that the researchers' "main emphasis was on testing editing rather than avoiding this disease," Church said.