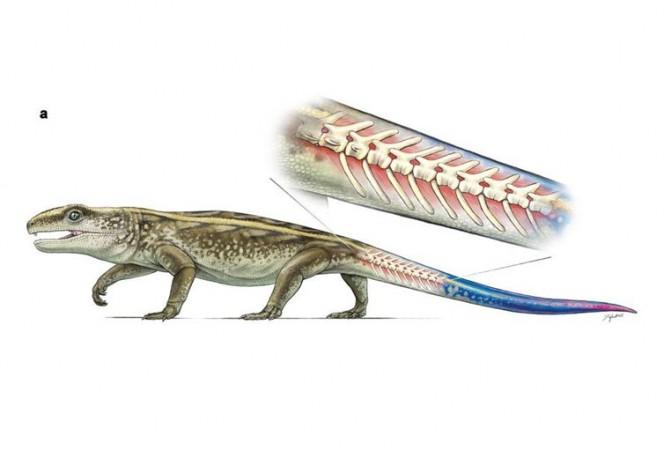

Many lizards that exist today use a unique trick to escape predators -- they drop a portion of the tail to fool their killer. Now, scientists have revealed that the oldest animal to demonstrate this behavior, known as caudal autotomy, was a small reptile that lived 289 million years ago.

This particular reptile, called Captorhinus, weighed less than two kilograms and was abundant in terrestrial communities during the Early Permian period. According to the study, published in the journal Scientific Reports on Monday, these reptiles were the first amniotes that could "autotomize" their tails as an anti-predatory behavior.

Captorhinus and its relatives had to scrounge for food while avoiding being preyed upon by large amphibians and mammals, and "one of the ways captorhinids could do this was by having breakable tail vertebrae," Aaron LeBlanc, a PhD student at the University of Toronto Mississauga and the study's first author, said in a statement.

"If a predator grabbed hold of one of these reptiles, the vertebra would break at the crack and the tail would drop off, allowing the captorhinid to escape relatively unharmed," Robert Reisz, a professor of biology at the University of Toronto Mississauga, said in the statement.

According to the researchers, captorhinids were the only reptiles at the time with such a unique escape strategy. However, the trait disappeared from the fossil record when Captorhinus died out, and re-evolved in lizards only about 70 million years ago.

As part of the study, the researchers examined over 70 tail vertebrae and partial tail skeletons featuring splits that ran through their vertebrae. After comparing these skeletons with those of other reptilian relatives of captorhinids, the researchers concluded that the ability to detach tails was limited to this family of reptiles in the Permian period.

Further analysis also revealed that the cracks, which were formed naturally as the vertebrae were developing, were well-shaped in young captorhinids while those in some adults tended to fuse up.

"This makes sense, since predation is much greater on young individuals and they need this ability to defend themselves," the researchers said.