NASA's Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR) launched its newest X-Ray telescope over the Pacific Ocean on Wednesday.

The telescope was launched in the morning light from the Kwajalein Atoll, the Pacific Ocean halfway between Australia and Hawaii at 9 a.m. PDT.

The pioneering new telescope, built by Orbital Sciences Corporation is launched to kick-start its two-year mission to unveil the secrets of obscured black holes and a whole variety of neutron stars and other things that haven't been discovered yet.

"It will help us find the most elusive and most energetic black holes, to help us understand the structure of the universe," Fiona Harrison, the mission's principal investigator at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, said in a statement.

In addition, it will also study other high-energy objects including the remains of exploded, compact, dead stars; and clusters of galaxies in the universe.

NASA's Astrophysics Division Director, Paul Hertz, said, "NuSTAR will open a new window on the universe and will provide complementary data to NASA's larger missions including Fermi, Chandra, Hubble and Spitzer."

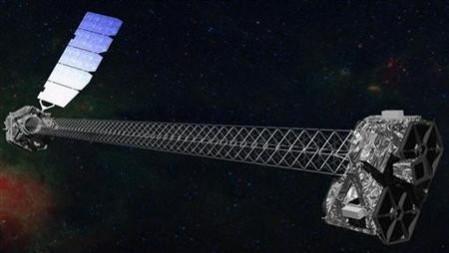

The new telescope has two sets of 133 concentric shells of mirrors and a 33-foot mast that will pull out once the spacecraft reaches the orbit, in about seven days from the launch. It will enable the telescope to focus properly on the masked black holes and stars.

Scientists claim that there is a gigantic black hole in the center of every big galaxy but are masked by gas or dust.

"We're pretty sure that every big galaxy has a super-massive black hole in its center and the models predict that most of the ones that are actively accreting material and get very bright are being hidden by gas and dust around them," NuSTAR project scientist Daniel Stern told Reuters.

"With these observations, we'll get a better idea of the physics of supernova explosions," he said.