India's biggest indirect tax reforms set to go on stream next month open new directions towards unified and simplified taxation, while dishing out a fresh set of ironies on the pricing front. For, the hassles of creating a patina of simplicity in billing for the producer of goods through a slew of regulations could be offset by some inscrutable results for the buyer.

One of the most eye-catching colours in the new bouquet of tax regulations are the hallowed price-tags of premium luxury cars dropping a few sundry lakhs. But the small car segment, which comprises roughly 70 per cent of the Indian car market, stands to gain little. Buyers of small petrol cars (which come with a 28 per cent GST slab) with 1.2 litres plus capacities will shell out 1 per cent more by way of a new cess, while a 3 per cent increase awaits small diesel car buyers. Whether this marginal increase is worth passing on to consumers will be determined by how Motown reads the final notification on GST rates.

Important items of daily use – the Volkswagens and Mercedes S classes rarely fall in this category – including hair shampoo, dye, after shaves, shaving creams, washing machines, ATMs, vacuum cleaners, automobiles and bikes will attract 28 per cent tax. Hardcore fans of GST would agree that clubbing a consumer specific like cinema with race club betting and 5-star hotels as avoidable luxuries deserving a 28 per cent tax slab slapped on them hardly makes sense as a business reform, not to mention a "lifestyle reform".

Disincentivising consumption

The idea was to introduce GST at a uniform rate of taxation, an indirect tax applied to both goods and services. A single form of tax known as GST or Goods and Services Tax when being applied throughout the country would replace a number of other indirect taxes like VAT, service tax, CST and CAD, among others.

But the simplification and standardisation process may not come as cheaply as it is made out to be. While the cost of production for manufacturers will be effectively pruned along with the procurement and logistics costs of the finished goods, the cost of services associated with the sales of these products will go north. As a consequence, the additional cost of GST could negatively impact consumer price inflation and the ability of consumers to pass on tax benefits to their consumers.

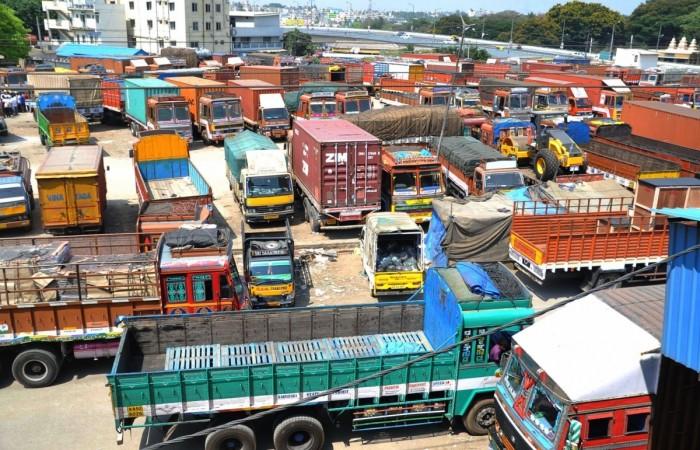

Critics have for good reason pointed out that the existing system taxes production more than consumption. This, in effect, subsidises importers at the expense of the domestic producers who are more vulnerable to factors like raw material costs and foreign exchange fluctuations. The central sales tax of 2 per cent has hindered trade between states for long. The GST regime was meant to shorten the long lines of goods-laden lorries biding their time (and money) at state border checkposts across the country. GST's biggest promise is held out on this front.

Cess, not desist

The cess factor could turn out to be GST's shark tooth. Whether it strikes blood remains to be seen, though its murderous effect on the consumer's wallet could be making its presence felt already. Under the new GST regime, the government is categorising 1,211 items under various tax slabs with a bulk of them figuring under the predominantly 18 per cent cess pool. The effective tax rates on approximately 75 per cent of these items would be in the 18-22 per cent range.

The devious roles played by cesses in inflating prices in a post-GST regime is amply clear in the case of the luxury car market. Cap the cess at 15 per cent and you get a cascading 10 per cent reduction in final prices. The way cesses are manipulated going ahead will make or break GST in the public perception.

Let's not forget that service tax through a plethora of cesses has been imposed subtly down the years. Available data indicates that in 2002, the service tax rate was just 5 per cent on just 52 defined services. By 2010, the effective service tax rate had more than doubled to 10.3 per cent and covered 119 services. And in 2016, the effective service tax that you paid was at 15 per cent and covered all services.

So, are we really paying higher service taxes than earlier? Indeed, it would appear so. Even if the competition among different states to bring down cost of producing manufactured goods does result in higher investments and employment generation, the expected positives from tweaking cesses through the GST route may not make their presence felt in the consumer's wallet. If and when it happens, that will be the litmus test.