Dinosaurs may have gone extinct, but they continue to live on in some form through their descendants: birds. The analysis of thousands of fossils–both dinosaurs and birds–over the years has revealed that these reptilians underwent numerous transformations to give rise to avians. Now, scientists have discovered the remains of a 'bizarre' ancient bird that offers new insights into this fascinating evolution–one with a dinosaur's head and a bird's body.

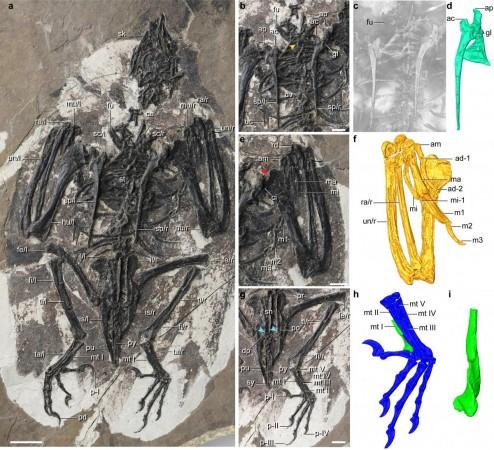

In a new study, palaeontologists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences have described a species of primitive bird that was unearthed in China. Named Cratonavis zhui, the avian lived around 120 million years ago during the Cretaceous period. In addition to its dinosaur-like skull, Cratonavis was also found to have an unusually elongated shoulder blade and toe bone, making it an exception among all birds known to have existed, including fossilised ones.

"We report an Early Cretaceous non-ornithothoracine pygostylian, Cratonavis zhui gen. et sp. nov., that exhibits a unique combination of a non-avialan dinosaurian akinetic skull with an avialan post-cranial skeleton, revealing the key role of evolutionary mosaicism in early bird diversification," wrote the authors. The findings were published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

A Dinosaur-like Skull

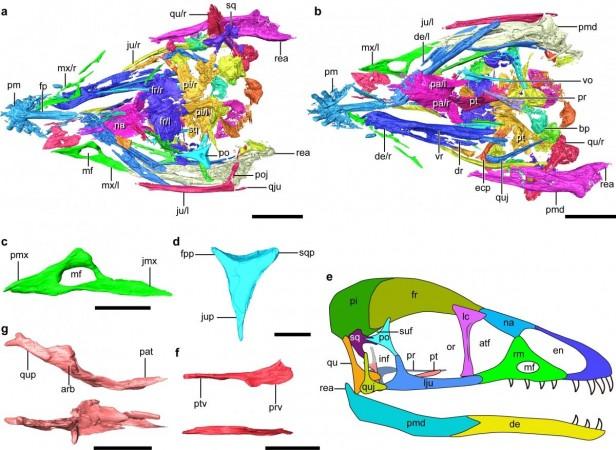

In order to examine the petrified remains of Cratonavis zhui, the team utilised an advanced scanning technique known as high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). Next, they digitally separated the bones from the solid mass and reconstructed the skeleton to its original shape and function.

Through the investigation of the Cratonavis skull, the researchers made an exciting discovery: the skull did not morphologically resemble that of birds. In fact, it was nearly similar to the skulls of dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus rex and Tarbosaurus.

Explaining the construction of the skull, Dr. Li Zhiheng, lead author of the study, said in a statement: "The primitive cranial features speak to the fact that most Cretaceous birds such as Cratonavis could not move their upper bill independently with respect to the braincase and lower jaw, a functional innovation widely distributed among living birds that contributes to their enormous ecological diversity."

A Shoulder Blade Like No Other

In addition to the unique skull, Cratonavis the specimen also possessed an uncharacteristically elongated scapula (commonly referred to as the 'shoulder blade'). The finding is crucial as this bone plays a key role in avian flight and provides birds with flexibility and stability.

"We trace changes of the scapula across the Theropod-Bird transition, and posit that the elongate scapula could augment the mechanical advantage of muscle for humerus retraction/rotation, which compensates for the overall underdeveloped flight apparatus in this early bird, and these differences represent morphological experimentation in volant behaviour early in bird diversification," stated Dr. Wang Min, corresponding author of the study.

Evolution of the Avian Feet

Cratonavis was also found to have an uncommonly elongated first metatarsal, a bone located behind the big toe. According to the authors, the first metatarsal underwent selection during the transitioning 'dinosaurs-bird' phase where a shorter bone was favoured. Ultimately, the first metatarsal's evolutionary lability (the characteristic of undergoing continuous change) disappeared when it achieved its ideal size– less than 25 percent the length of the second metatarsal (found in the second toe).

Dr. Thomas Stidham, a co-author of the study, noted: "However, increased evolutionary lability was present among Mesozoic birds and their dinosaur kins, which may have resulted from conflicting demands associated with its direct employment of the hallux in locomotion and feeding." The authors posit that in the case of Cratonavis, it is likely that an elongated hallux, or the 'big toe', was a result of selection for raptorial behaviour (i.e) to grab prey.

According to Dr. Zhou Zhonghe, another co-author of the study, the atypical structures of the scapula and metatarsals observed in Cratonavis draw attention to the extent of skeletal plasticity found in early birds. So where does find Cratonavis find itself in the evolutionary tree? It has been placed between Archaeopteryx, a genus of feathered dinosaurs, and Ornithothoraces, a group of birds consisting of both modern and extinct birds.

![Nothing to open its first global flagship store in THIS Indian city [details]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/827007/nothing-open-its-first-global-flagship-store-this-indian-city-details.png?w=220&h=138)