An international team of scientists have unveiled the first dinosaur that really "took to the water". The newly discovered fossils of Spinosaurus, the massive Cretaceous-era predator, reveal that it had adapted to a life in water around 90 million years ago. It is the most compelling evidence to date, of any dinosaur that could hunt in an aquatic environment.

The fossils also revealed that the Spinosaurus was at least nine feet bigger than the world's largest T Rex dinosaur, making it about 50 feet long and was an excellent swimmer, unlike any other dinosaurs unveiled so far. Found in the sands of Morocco, the bones of Spinosaurus suggest that, unlike its land-dwelling cousins, this meat-eating predator likely fed on sharks and other fish.

An international research team, consisting of National Geographic Emerging Explorer and palaeontologist Nizar Ibrahim, Prof. Paul Sereno from the University of Chicago, Cristiano Dal Sasso and Simone Maganuco from the Natural History Museum in Milan, Italy; and Samir Zouhri from the Université Hassan II Casablanca in Morocco, published these findings regarding Spinosaurus on the Science Express on 11 September.

The first bones of Spinosaurus, named after its long spines, which stretch up to almost seven feet, was uncovered by the German paleontologist Ernst Freiherr Stromer von Reichenbach in the Egyptian Sahara in 1912. However, the bones were destroyed in World War II, leaving paleantologists with nothing more than a shadow of the Spinosaurus.

This team of researchers depended on the historical images of the first discovery of Spinosaurus bones from a century ago, new fossils uncovered in the Moroccan Sahara and a partial Spinosaurus skull and other remains housed in museum collections around the world, before arriving at their conclusions.

Aquatic adaptations of Spinosaurus differ significantly from earlier members of the spinosaurid family that lived on land but were known to eat fish.

They have small nostrils located in the middle of the skull to breathe when part of its head was in water, neurovascular openings at the end of the snout similar to that of crocodiles and alligators, giant, slanted teeth that interlocked at the front of the snout, that are well-suited for catching fish, powerful forelimbs with curved, blade-like claws that were ideal for hooking or slicing slippery prey, a small pelvis and short hind legs with muscular thighs for easily paddling in water, strong, long-boned feet and long, flat claws and enormous dorsal spines covered in skin that created a gigantic "sail" on the Spinosaurus' back.

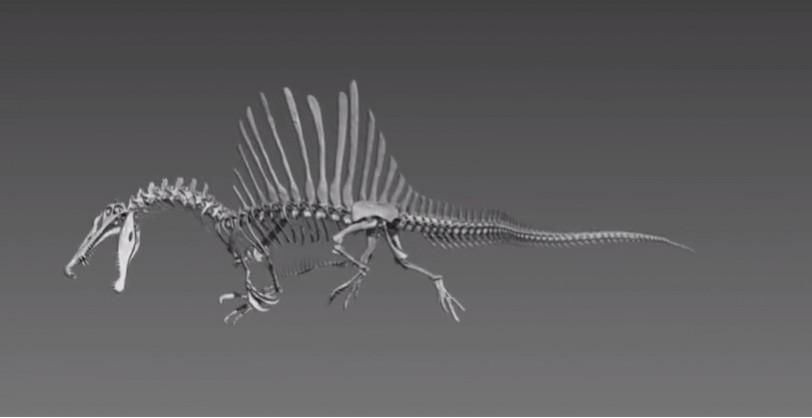

To unlock the mysteries of Spinosaurus, the team also created a digital model of the skeleton with funding provided by the National Geographic Society. "We relied upon cutting-edge technology to examine, analyze and piece together a variety of fossils. For a project of this complexity, traditional methods wouldn't have been nearly as accurate," revealed Maganuco.

The researchers also used the digital model to create an anatomically precise, life-size 3-D replica of the Spinosaurus skeleton. After it was mounted, the researchers measured Spinosaurus from head to tail, confirming their calculation that the new skeleton was longer than the largest documented Tyrannosaurus Rex by more than 9 feet.

To learn more about the first aquatic dinosaur, click here and for details about visiting the exhibit at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C., through April 12, click here.

Watch University of Chicago paleontologist Paul Sereno describing the project that led to the conclusions regarding Spinosaurus in this video.