Cancer is the second-leading cause of death in the world and there's no absolute cure for the deadly disease. With medical advancements, the survival rates are improving for many types of cancers. Still, it is a long road ahead to promise cancer patients a complete cure. But a clinical trial involving a small group of rectal cancer patients has delivered unprecedented results.

"I believe this is the first time this has happened in the history of cancer," Dr. Luis Alberto Diaz, Jr., a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Cancer Center who also led the trial, was quoted as saying by NYTimes.

It was a small trial involving 18 rectal cancer patients, who were treated with an experimental drug. The result: Every last patient who took the drug experienced complete remission. The study found that cancer had vanished from every patient's body, with no traces found even after physical examination, PET Scan, MRI, or Endoscopy.

"There were a lot of happy tears," the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) and a co-author of the paper, oncologist Dr Andrea Cercek, said recalling the moment when the patients heard the news.

The paper was published in the New England Journal of Medicine by Dr. Luis A. Diaz Jr. of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The study was sponsored by the drug company GlaxoSmithKline.

An unprecedented clinical trial

Fetching 100 percent remission in a cancer trial is unheard of. This is truly historic. All the 18 patients in the trial took 500mg of a drug called Dostarlimab every three weeks for six months. Initially, the expectation was that most of the patients would still require a standard combination of chemotherapy, radiation therapy and potentially surgery. But to their surprise, the cancer was obliterated in every patient on Dostarlimab alone.

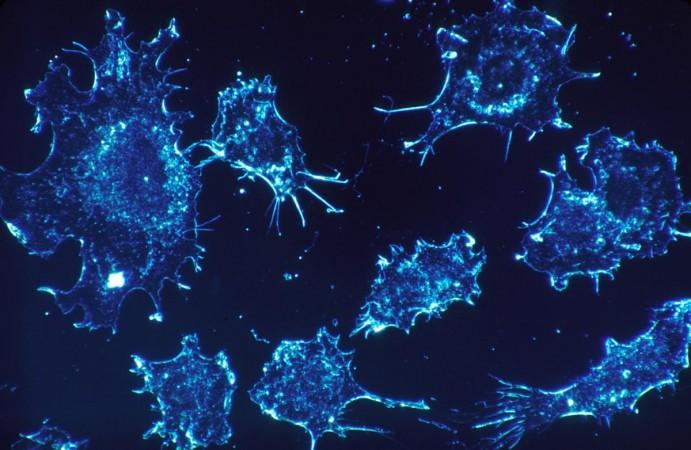

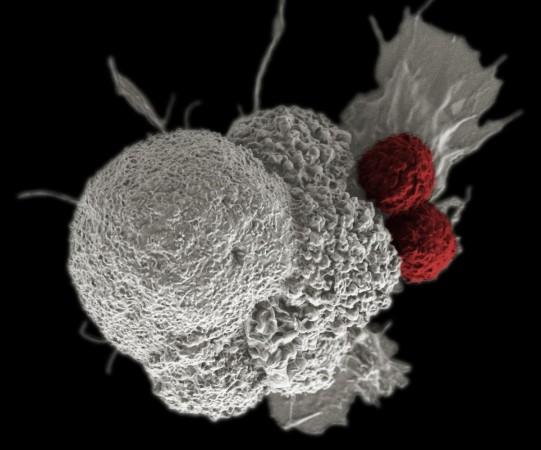

The Dostarlimab, also known as checkpoint inhibitors, unmasks cancer cells, allowing the immune system to identify them and destroy them.

A year later, diagnosis tests were repeated and none of the patients had relapsed. In fact, more than two years have passed and "no patients have required chemoradiation or surgery, and no cases of progression or recurrence have been noted during follow-up," a statement from MSK said.

While nothing matches the feeling of hearing the words "cancer-free", the patients didn't have any significant complications during the trial. One in five patients usually have some sort of adverse reactions to drugs like Dostarlimab, but the trial was exceptional. All patients who participated in the trial were in similar stages, and the cancer had been locally advanced in the rectum and hadn't spread to other parts.

Is it a cure?

It's too soon to tell. Naturally, a larger trial is necessary to draw conclusions. It will help gauge the effectiveness of the drug. But these results are truly remarkable and instil a sense of hope. Patients with rectal cancer are usually less responsive to chemotherapy and even radiation treatments. The next viable option is surgical removal of the tumour, which can be life-altering with bowel, urinary and sexual dysfunction.

"These results are cause for great optimism," but without further research, dostarlimab cannot yet replace the standard, curative treatment for mismatch repair-deficient rectal cancer, Dr. Hanna Sanoff, an oncologist at the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina, wrote. She added that in some patients the response to checkpoint inhibitors can last for years, but also wear off much quickly in others.

"Very little is known about the duration of time needed to find out whether a clinical complete response to dostarlimab equates to cure," Sanoff added.

Regardless, this new approach of "immunoablative" therapy offers a promise of curative treatment. "If immunotherapy can be a curative treatment for rectal cancer, eligible patients may no longer have to accept functional compromise in order to be cured," she said.