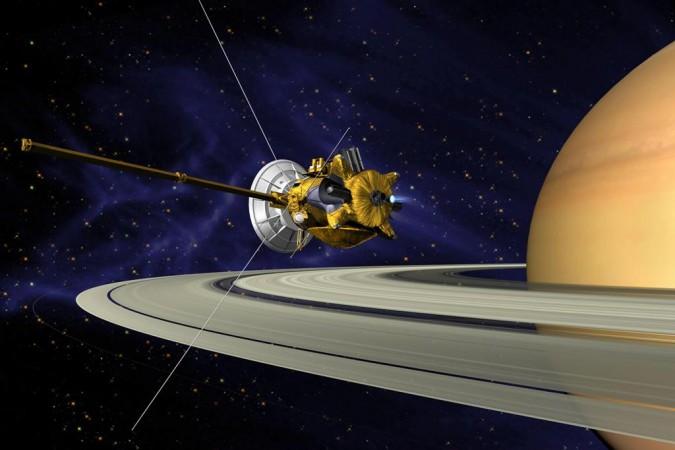

NASA's Cassini spacecraft ended its 13-year tour of Saturn when it plunged into the atmosphere of the ringed planet on Friday. According to the federal space agency, it lost contact with Cassini at 7:55 am EDT, with the final signal from the spacecraft received by NASA's Deep Space Network antenna complex in Canberra, Australia.

"This is the final chapter of an amazing mission, but it's also a new beginning," Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, said in a statement. "Cassini's discovery of ocean worlds at Titan and Enceladus changed everything, shaking our views to the core about surprising places to search for potential life beyond Earth."

Launched in 1997, Cassini arrived at Saturn in 2004. NASA extended the spacecraft's mission twice – first for two years and then for seven more years.

According to scientists, the final set of observations made by Cassini during the last few days of its tour of Saturn are expected to offer new insights about the plant's formation and evolution, as well as the processes occurring in its atmosphere.

Let's have a look at Cassini's last images, which include a view of the site of the spacecraft's atmospheric entry.

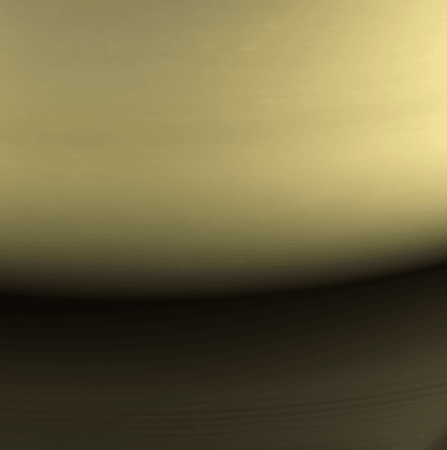

Impact Site: The final image

This is the last image taken by Cassini's imaging cameras on September 14 at 19:59 UTC (spacecraft event time). The image, which was taken using Cassini's wide-angle camera at a distance of 634,000 kilometres from Saturn, shows the planet's night side -- lit by reflected light from the rings -- and the location at which the spacecraft later entered Saturn's atmosphere.

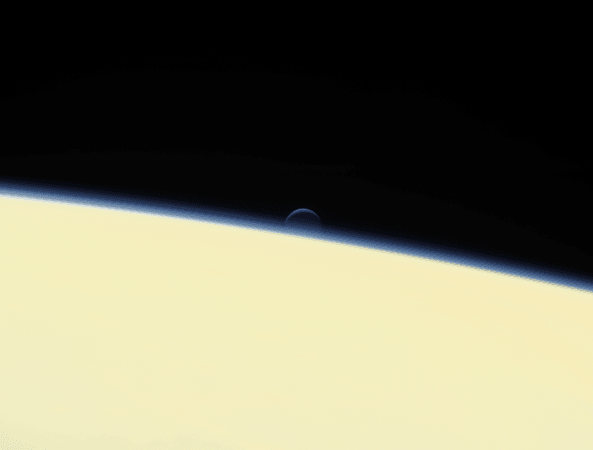

Sinking Enceladus

Taken on September 13, this image shows Saturn's active, ocean-bearing moon Enceladus setting behind the ringed plant. Cassini captured the image using its narrow-angle camera at a distance of 1.3 million kilometres from Enceladus, and about 1 million kilometres from Saturn.

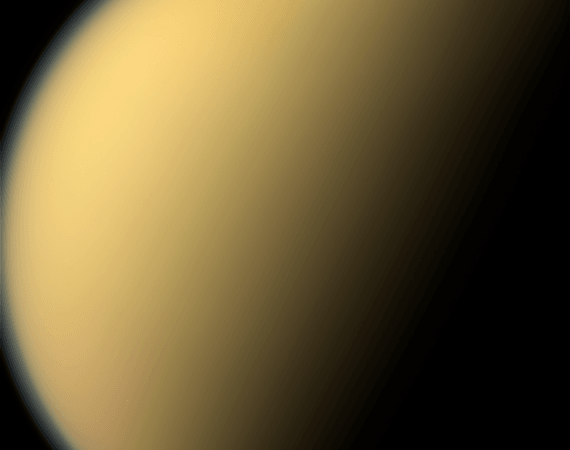

The final glance at Titan

This image of Saturn's giant moon Titan was taken using Cassini's narrow-angle camera on September 13. The spacecraft was at a distance of 774,000 kilometres from Titan when it captured the image.

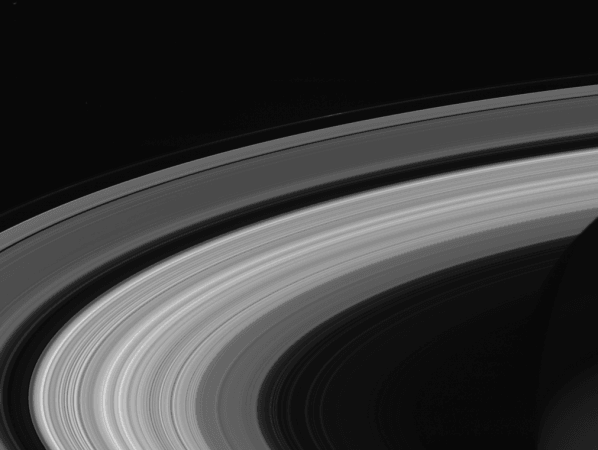

The rings, one last time

Taken from a distance of 1.1 million kilometres from Saturn, this the final view of Saturn's famous rings captured by Cassini on September 13.

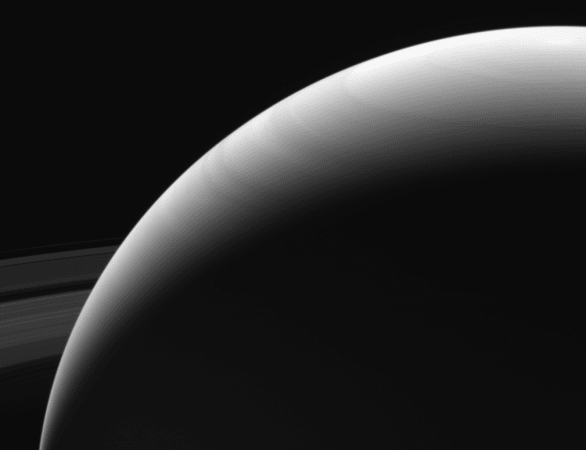

The northern Saturn

This image of Saturn's northern hemisphere was also captured on September 13. Cassini was 1.1 million kilometres away from the planet when it took this photograph.

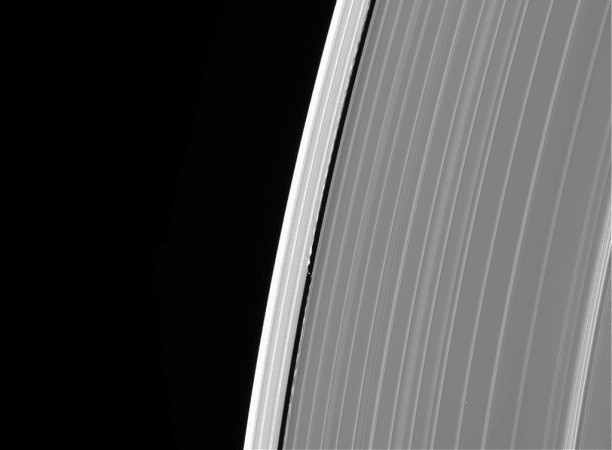

Tiny Daphnis' final appearance

Taken on September 13, this image of Saturn's outer A ring features the small moon Daphnis. Also visible are the waves the tiny natural satellite raises in the edges of the Keeler Gap. The image was captured when using Cassini's wide-angle camera at a distance of 782,000 kilometres from Saturn.

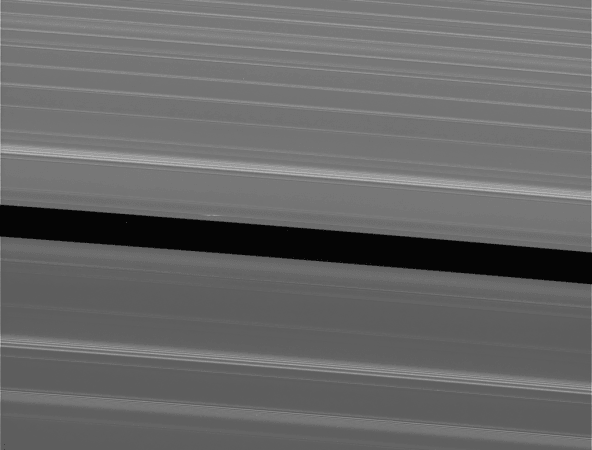

Lone Propeller

This is a view of Saturn's A ring, showing a lone "propeller" trying, unsuccessfully, to open a gap in the ring material. Propellers are disturbances caused by small moonlets embedded in Saturn's rings. Cassini captured this image on September 13, at a distance of 676,000 kilometres from the planet.

Although Cassini has ended its journey, the enormous collection of data that it had collected about Saturn and its moons is expected to continue to help astronomers yield new discoveries in the future.

"Cassini may be gone, but its scientific bounty will keep us occupied for many years," Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA, said in the statement. "We've only scratched the surface of what we can learn from the mountain of data it has sent back over its lifetime."